The European Court of Justice (CJEU) is the highest court in the European Union. Decisions regarding video games are few and far between. So when he governs, we hope the decision will be a game changer.

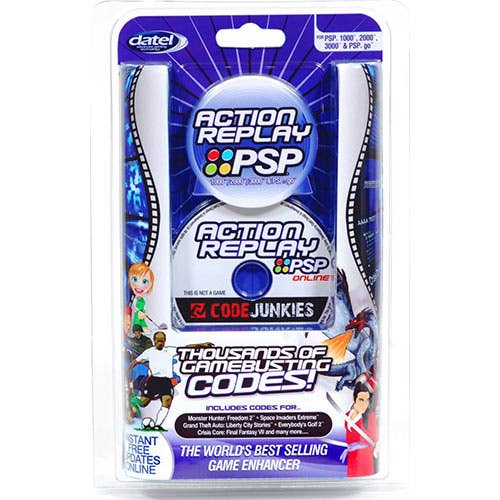

The ruling he issued on October 17, 2024 (ruling against Sony in a dispute over cheating provided through Datel’s Action Replay for PSP) seems like one at first glance. A second look shows that in most cases this will not change anything. The reason for this is that lawsuits against developers of cheating software, especially in online multiplayer games, are now based on violations of game developers’ EULAs and competition law.

The case of the ECJ, however, is different. These are the Action Replay PSP and Tilt FX PSP software, which gave superpowers to several games on Sony’s now almost forgotten Playstation Portable. Sony initially won an injunction in 2010 before the Hamburg Regional Court, as well as the case on the merits two years later. The trap producer filed an appeal and the decision was overturned nine years later, in 2021.

The German Federal Court of Justice then referred the case to the ECJ. National courts can do this if they have doubts about the interpretation of EU law. As a reminder: Germany’s Federal Supreme Court (Bundesgerichtshof) had already issued two rulings on cheating for World of Warcraft (as of October 6, 2016 – case I ZR 25/15, and as of January 12, 2017 – case I ZR 253/14).

When the German Federal Supreme Court brought the case to the ECJ, it is not because the judges have changed their minds and become friendly to cheaters in the meantime. It was because the relevant question of law was another. The question was whether Action Replay PSP and Tilt FX PSP infringe copyright even though they did not interfere with the source code or the software itself, but simply modified variables in the computer’s RAM. The CJEU held that this is not sufficient to constitute copyright infringement.

The issues that were relevant in the World of Warcraft cases simply weren’t on the table here (this could have something to do with the fact that Action Replay was taken to court almost 15 years ago, when it might not have been so clear what tools publishers have against cheating bots, and also with the fact that it is not about cheating in a multiplayer game).

For single-player game publishers looking to take action against cheating software, the European Court of Justice’s decision on Action Replay is not good news. According to the CJEU, playing games is not necessarily a copyright infringement if the game software is not touched.

For single-player game publishers who want to take action against cheat software, the ECJ Action Replay decision is not good news.

However, there are still some instruments left: for example, offering this type of cheating could still be an act of unfair competition. This aspect was only briefly discussed in the German Action Replay rulings, and not at all by the ECJ. This aspect is especially relevant for games monetized through microtransactions.

It might also be possible to validly agree in the EULAs that the game should not be used with cheat software. This aspect was only mentioned in a side note by the Advocate General in the Action Replay decision and, for procedural reasons, did not appear in the German decision or the ECJ decision. Finally, depending on the name of the cheat software, it may infringe trademarks or title rights.

Multiplayer game publishers will have less to worry about. Cheats for online multiplayer games have been declared illegal by numerous courts. One of the most famous cases is Bungie vs. AimJunkies. While this was decided in the US, there is no reason to assume that the outcome would have been different in the EU, either before or after Action Replay.

This has been confirmed by the German Federal Supreme Court in its two previous rulings on World of Warcraft, as have other courts. These two decisions are not questioned by the new CJEU decision, since the issue is different. From the perspective of most players, because World of Warcraft decisions are specifically for online multiplayer games.

One of the World of Warcraft decisions addressed the question of whether the manufacturers who had developed the cheat software had the right to use World of Warcraft for commercial purposes, that is, the development of the cheat software (which is a discussion based on copyright law). . The other decision revolved around the question of whether the impact of the respective hack on the game was an unfair interference and prevented Blizzard from presenting its game on the market in the form originally intended (this is an argument based on unfair competition law).

The first of these issues was not discussed in the Action Replay cases, and for the second, Sony did not present sufficient evidence. Therefore, publishers of online multiplayer games can still rely on established case law when acting against cheating software.

Additionally, there are many other aspects that may be relevant, depending on the details of the case at hand (such as complicity in copyright infringement by users who play the game in violation of the EULAs by using cheat software, circumvention of technological rights, protection measures or modification of the appearance of the game).

Publishers of online multiplayer games can still rely on established case law when taking action against cheating software.

Now, finally, did it matter that Action Replay was litigated in Europe and Bungie v. AimJunkies in the United States? Presumably not so much. The issues relevant to litigating against cheating robots in multiplayer games are essentially similar, although the legal traditions and procedure are different.

Publishers have a wide choice in taking these matters to court. Suing violators where they are may be a logical option. Facilitates the execution of judicial decisions against the offender. The geographical scope of the decisions of the court in which the offender is located is also potentially broader.

However, there could be other aspects to consider, for example how robust and fast the legal system is, or the respective costs. Germany, for example, has abundant case law and courts tend to quickly issue interim measures. In the United States, however, the procedures may be more expensive, but it may be easier to obtain that missing information through discovery. Therefore, there are many aspects to consider.